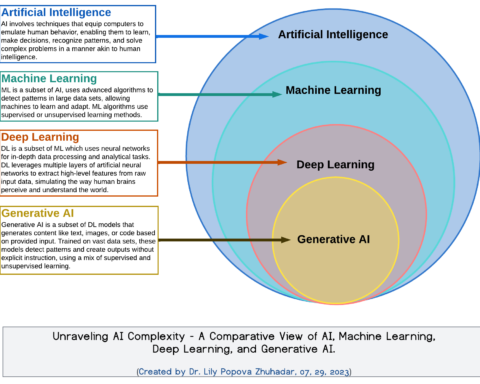

There is no silver bullet for striking a fair balance in power between everyday consumers and large corporations in the age of big data and surveillance capitalism. The Australian Government is investing $65 million to reform the country’s antiquated data ecosystem to address some of the existing inequities that shortchange consumers.1 A key feature of these reforms is a new Consumer Data Right (‘CDR’) legislated under Part IVD of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) to confer upon citizens greater control and transparency over their own data.2 In this new data policy’s crosshairs are the so-called information asymmetries that create power imbalances in favour of corporations with the ability to leverage their vast and oftentimes intimate knowledge of potential or existing customers to influence their spending habits.3

The CDR scheme aims to tip the scales back in favour of consumers by simplifying an individual’s search associated with switching providers by creating automated price comparisons.4 In theory, this will stimulate market competition by giving more information to consumers about the corporations they are dealing with to reduce the asymmetry in knowledge and level the playing field.5 Information asymmetries have long been a point of contention as a cause of anti-competitive behaviour but government interventions to correct the invisible hand in a free market economy have historically been met with scepticism.6 Nevertheless, Faure and Luth noted that government intervention is only necessary to correct market failures and ‘[t]he most important market failures in the area of consumer policy are information asymmetries and transaction costs.’7

The CDR’s open data-sharing requirements are currently rolling out across the banking sector, followed by the energy and telecommunication sectors, before being applied to the wider economy.8 This means we can only assess preliminary data on the efficacy of the scheme in the sectors in which the roll-out has commenced, though the analysis of results so far is mixed. The banking industry, in particular, has come under damning criticism that may reach the threshold to which Faure and Luth advocate for government intervention to address the market failure caused by information asymmetries. The Hayne Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking Industry excoriated the way consumers were oftentimes unable to make well-informed choices between providers due to a ‘marked imbalance of power and knowledge between those providing the product or service and those acquiring it.’9 This power imbalance between financial institutions and consumers was exacerbated by the lack of practical options for consumers in alternative banking services.10

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (‘ACCC’) also believes a prime factor leading consumers to disengage from the energy market is due to insufficient information about available alternatives despite the fact that healthy markets require engaged customers with access to accurate information.11 In its Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry (‘REPI’), the ACCC made 56 recommendations for the energy industry, of which the 31st recommendation was the introduction of the CDR for energy.12

The CDR scheme can potentially empower customers in this sector by providing them access to their electricity data which will in turn help them navigate the market and negotiate better deals.13 Nevertheless, consumers are complex, and analysis from behavioural economics has demonstrated that placing too much information on a platter can lead to ‘choice paralysis’ for consumers.14 The literature on behavioural economics suggests that subtle and subconscious cognitive biases which dictate individual behaviour may scupper the CDR scheme’s best intentions.15 This means the technical design and deployment of the CDR must ensure that third-party access to data does not duplicate or complicate data access methods already available.16 There is also a risk of conflict between current energy rules and the newly implemented CDR rules in this sector.17

The four guiding principles of the CDR is that it should be consumer-focussed, encourage competition, create opportunities, and be efficient and fair.18 To ensure the CDR is true to its guiding principles, regulatory bodies must keep watch over the various actors in the scheme to prevent price gouging and deceptive behaviour. The ACCC has already taken enforcement action against iSelect, Energy Watch, and Compare the Market, for false and deceptive representations on price comparisons.19

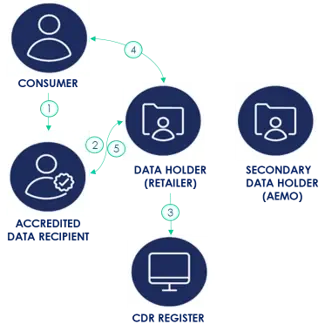

The CDR scheme is primarily established with amendments to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), while amendments to the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010 (Cth) and the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) establish regulatory and privacy safeguards under the ACCC, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) and a newly created Data Standards Body.20 At the heart of the CDR legislation is the right of consent, which bestows upon the consumer ‘a right to give instructions about how one’s data is collected, stored, and used.’21 Leach and McKay have noted that this will have flow-on effects for other possible data rights for consumers in Australia, including rights already enshrined in Europe’s GDPR data laws, such as the right to privacy and the right to be forgotten.22 However, without appropriate privacy safeguards enforced by regulatory watchdogs with teeth consumers may be subject to even more invasive privacy breaches.

An actor in the CDR scheme such as a Price Comparison Website (‘PWC’) may compile insights and construct profiles or digital dossiers on their customers in contravention of s 4.12(3)(i)(ii) of the CDR Rules.23 As the designated regulatory body, the ACCC must police these privacy breaches and ensure the data minimisation principle in s 1.8 as well as the right to delete discussed in Subdivision 4.3.4.24

The CDR Data Standards also include standards for information security practices, securing Application Programming Interfaces, as well as following user experience guidelines.25 Additional privacy measures include the CDR policy’s 13 Privacy Safeguards that broadly mirror the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) in the Privacy Act (1988)(Cth).26 Critics believe this may create difficulties when distinguishing whether data is subject to the CDR Privacy Safeguards or the APP’s in the Privacy Act.27 For instance, the restrictions on compiling insights in relation toa user in the CDR may correspond to restrictions in the Australian Privacy Principle 6 on using information for a secondary purpose.28

This analyses concludes that from a technical and policy standpoint, the CDR has the potential to empower the consumer by reducing information asymmetries through dashboards and consent forms and third party price comparisons. However, if the CDR scheme fails to strike the correct balance that empowers individuals over corporations, the policy may only further muddy the waters of an already complex data ecosystem and lead consumers to further disengage.

- Commonwealth of Australia, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, The Australian Government’s response to the Productivity Commission Data Availability and Use Inquiry. ↩︎

- Idib. ↩︎

- Hayne, Final Report: Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (2019) Volume 1, 2 (‘Hayne Royal Commission’). ↩︎

- Treasury, Consumer Data Right Overview (2019). ↩︎

- Scranton, ‘The Consumer Data Right: Right for competition in Australian retail energy markets?’ (2020) 27 CCLJ 107, 132 (‘CDR: Right for competition?’). ↩︎

- Stefan Mann, Henry Wüstemann, ‘Public governance of information asymmetries—The gap between reality and economic theory’ (2010) 39(2) The Journal of Socio-Economics 278, 285. ↩︎

- Michael G Faure and Hanneke A Luth, ‘Behavioural Economics in Unfair Contract Terms’ (2011) 34(3) Journal of Consumer Policy 337, 340. ↩︎

- Jamie Leach and Julie McKay, ‘The Australian Consumer Data Right: the Promise of Open Data’ in Linda Jeng (ed), Open Banking (Oxford University Press, 2022) 202. (‘CDR: Promise of Open Data’). ↩︎

- Hayne Royal Commission (n 12) 2. ↩︎

- CDR: Promise of Open Data (n 17) 203. ↩︎

- ‘What Does Behavioural Economics Mean for Competition Policy?’ (n 3) 10–11. ↩︎

- ACCC, REPI (n 18) iv. ↩︎

- Treasury (Cth), Consumer Data Right Overview (September 2019) 1. ↩︎

- Pete Lunn, ‘Regulatory Policy and Behavioural Economics’ (Paper, 9th Meeting of the Regulatory Policy Committee, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 12–13 November 2014) 9. ↩︎

- CDR: Right for competition? (n 14) 135. ↩︎

- Ibid 120. ↩︎

- Ibid 119. ↩︎

- Treasury, Review into Open Banking: giving customers choice, convenience and confidence, Dec. 2017 (the First Farrell Review). ↩︎

- CDR: Right for competition? (n 14) 123-124. ↩︎

- CDR: Right for competition? (n 14) 115. ↩︎

- Idib. ↩︎

- Idib. ↩︎

- CCR 2020 (Cth)(n 1) s 4.12(3). ↩︎

- Idib 204. ↩︎

- Idib 205. ↩︎

- Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) s 56ED. ↩︎

- CDR: Promise of Open Data (n 6) 206. ↩︎

- Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) sch 1. ↩︎