Everybody has an identity and that identity is sacred to their sense of self. An individual needs an identity to perform the most basic of day to day functions from carrying a driver’s license while driving a car to purchasing supermarket groceries with their bank debit card. Life milestones require the identity we carry with us from birth whether it’s for baptisms and Bar Mitzvahs or whenever a wedding celebrant enters a loving couple’s identification into a government register for Births, Deaths and Marriages. An adolescent is keenly aware that an identity can grow and change over time, especially after passing their Learner ‘L’ Plates or getting a proof of age card that allows them to stride past the pub’s security guard and buy their first beer as an adult. Universities take identity extremely seriously because cheating on a test by having a much brighter student momentarily commandeer one’s login credentials is grounds for immediate dismissal. Furthermore, fibbing on a resume about false qualifications or former employment is severely frowned upon, so much so that recruitment agencies are often tasked with performing background checks on an applicant’s identity for due diligence. Workplaces nowadays also require security clearances or police checks to cross-match identification documents to prove you are who you say you are against a database of criminal records. Nevertheless, this still might not stop a disgruntled employee from logging on to a server with elevated privileges that belong to a supervisor for curiosity’s sake or financial gain. Perhaps the employee is under financial strain and their identity is associated with a poor credit rating which means financial institutions have refused to grant a mortgage.

Identity is the social adhesive that makes society work. Identity can be set in stone but can also be fluid. There is now a heated debate over identity and its intersection between race, gender, sexuality and socioeconomic status in the media and social science departments of cultural institutions. A different debate is also being waged by ethicists and privacy advocates to draft legislation on ‘The right to be forgotten’ which protects identities from intrusive search engine algorithms (Bertram et al., 2019). There is no doubt identity is a complex concept, and can mean many different things to many different people, but in much less abstract terms its viewed through the eyes of the law like this: “Legal identity is concerned not so much with the internalised view of the identity that relates to a person’s sense of self or the externalised view that concerns the way that a person is viewed by others but with the way in which an accumulation of information distinguishes an individual from all others.” (Finch, 2007). Despite this definition, for victims of identity fraud, having your identity taken from you and used without consent in the commission of a crime is a deeply personal affair. Psychologically, there is much more at stake than losing a lifetime’s accumulation of information that society uses to distinguish yourself from other individuals.

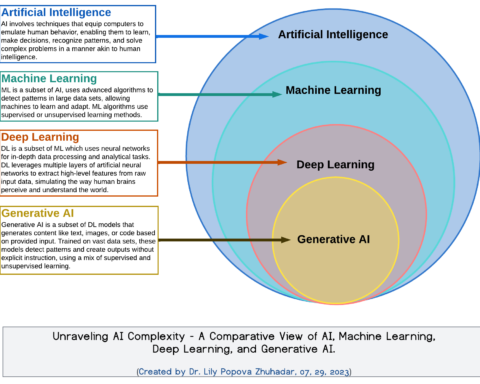

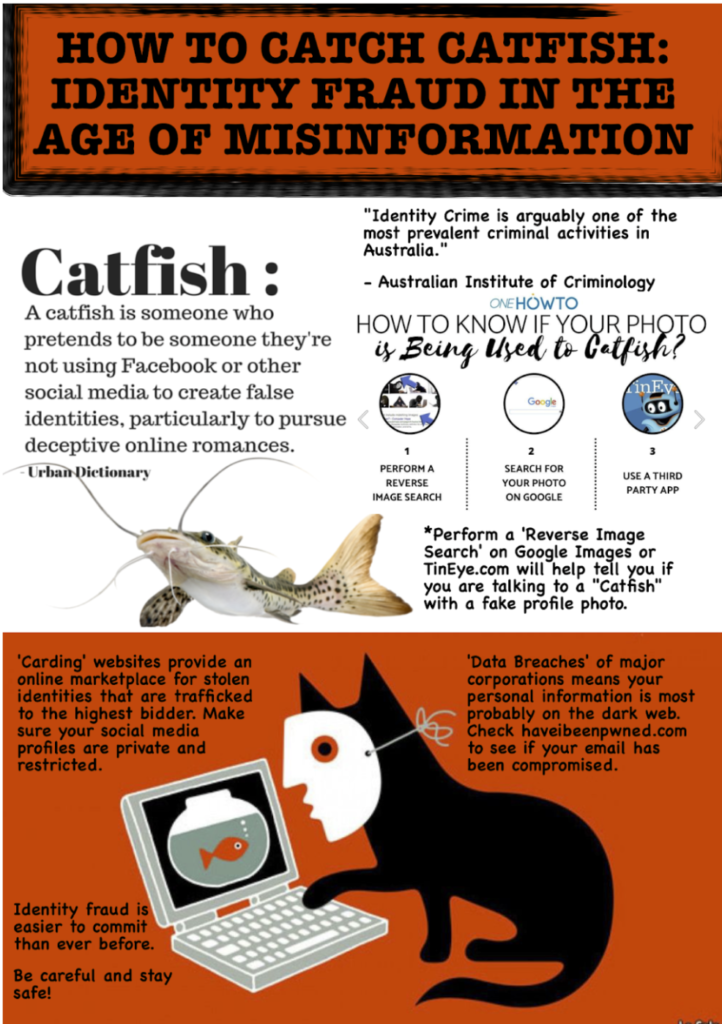

It is well known within law enforcement that crimes involving stolen, fake and fabricated identities often facilitate other forms of crime, from spear phishing to catfishing, money laundering and romance scams. The Berkeley Technology Law Journal noted that a piece of legislation in the United States called the Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act “covers conduct that could also be prosecuted under approximately 180 other federal criminal statutes” (Lynch, 2005). There are also subtle nuances between ‘identity fraud’, in which a perpetrator financially gains from using a stolen identity and ‘identity theft’, the act of trafficking stolen identities. Jonathan Clough also noted in the Principles of Cyber Crime that “Fraud itself is notoriously difficult to define, with technological changes only serving to cloud the issue further. For example, there is some debate as to whether payment card fraud should be regarded as a form of identity theft or recorded more generally as ‘fraud’” Furthermore, there is no single definition of identity crime, and the terms ‘identity fraud’ and ‘identity theft’ are often used interchangeably. Generally, however, identity fraud and identity theft both come under the umbrella of identity crime, which is the use of a false identity in the commission of a crime (Clough, 2015d, pp. 218, 229). This blog post will therefore explore the complexities of identity fraud using the criminological framework of Routine Activity Theory to explain how and why the crime occurs, its increasing prevalence and the prevention strategies of capable guardians, as well as what makes victims so vulnerable.

The victims of identity fraud are twofold: those who have their identity stolen and on the other side of the coin those who fall for stolen identities. In the United Kingdom, a 2012 survey found that 8.8% of UK adults had been victims of identity fraud in the previous twelve months, losing on average £1,203.137 which would mean an estimated loss of £3.3 billion. The UK fraud prevention service CIFAS recorded 123,589 cases of identity fraud, while 80% of identity-related crimes were enabled by the Internet. In 2013, Canada received 19,473 complaints of identity fraud, with losses totalling 11,078,565. Approximately 7% or 16.6 million Americans were victimized by identity theft, causing total and indirect losses of 24.7 billion USD and less than 9% of victims of identity theft in the United States reported to police. “Nonetheless, such statistics as there are indicated that online fraud in general, and identity crime in particular, are a significant problem.” Individuals and organisations may suffer reputational damage, including the downgrading of credit ratings or a range of emotional and psychological impacts such as the damage to relationships (Clough, 2015b, pp. 230–232). Back home, the Australia Institute of Criminology calls identity crime “arguably one of the most prevalent criminal activities in Australia, affecting individuals, businesses and government agencies. It is estimated that identity crime affects millions of Australians each year.” The most pronounced consequences related to mental and emotional stress, which increased nearly 12 percent between 2018 and 2019 (Franks & Smith, 2020).

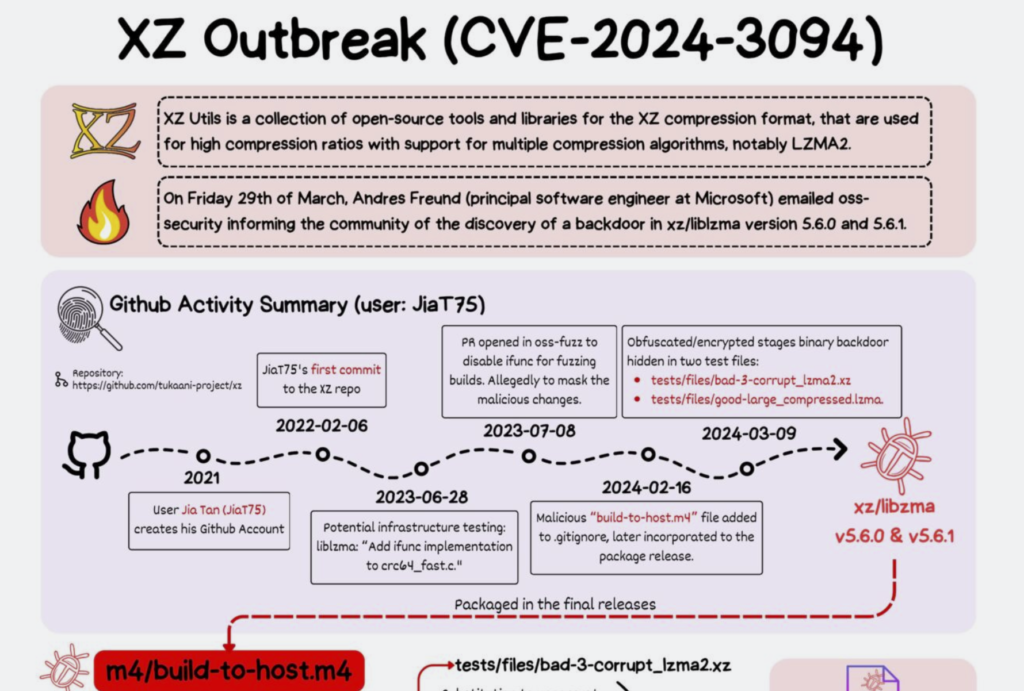

For criminals and organised crime there is no easier way to conceal one’s tracks than by appropriating a fabricated or stolen identity. “The internet provides anonymity. Offenders are not only able to conceal their real identities; they are able to assume realistic looking alternative identities” (Clough, 2015c, p. 211). Large scale data breaches of major corporations have flooded the dark web with a plethora of personal information and provided the perfect fodder for shadow data aggregators engaged in surveillance capitalism or the criminal networks committing fraud on an industrial scale (Peretti, 2008). Meanwhile, a rudimentary search on social media will reveal a wealth of intimate details which allow motivated fraudsters the ability to gain targeted personal information on potential victims with as much precision as staking out a house. Today, stealing an identity to commit fraud can be achieved much more effortlessly than ever before. Fake identities that facilitate romance scams and the emerging scourge of catfishing, a phenomena whereby fraudsters conceal their identity to lure unsuspecting victims, sometimes with the promise of love and often for financial gain, was almost nonexistent a little over a decade ago. Now constant vigilance and capable guardians are required to train people about the numerous ways in which an identity can be stolen, fabricated or technologically spoofed. Even forgery, once the staple of identity crime, has been transformed with digital technology and the advent of desktop publishing, photoshop, and colour scanners. The days that motivated offenders had to resort to dumpster diving and scrounging around garbage bins outside office buildings for discarded I.D. documents are also numbered since entire markets have emerged on the dark web that traffic in stolen identities. “So-called ‘carding’ websites facilitate the trade in identity information by providing an online marketplace” and owe their name to the acquisition, distribution, and use of stolen bank cards (Clough, 2015a, pp. 219, 227).

The interconnectedness of the modern world means it’s no longer science fiction for someone in a different timezone to steal your identity and not only commit fraud in your name but also cause irreparable harm to other unwitting victims. The interconnection which technology facilitates, however, has led criminologists to rethink the possible shortcomings of Routine Activity Theory’s approach to crime, which states that crime occurs at the intersection in space and time between a motivated offender and an accessible target in the absence of a capable guardian to intervene (Reyns et al., 2011). This approach to criminology made perfect sense when addressing street crime before the advent of the Internet but now an encounter in space and time is no longer required to commit an offense when everyone’s online. The intersection in which a motivated offender encounters a potential victim is no longer a dark street or train station without a security guard on patrol, it can happen on the mobile phones that we carry wherever we go. “The routine activity theory holds that the ‘organization of time and space is central’ for criminological explanation, yet the cyber-spatial environment is chronically spatio-temporally disorganized.” (Yar, 2005).

Modern scholars note that a combination of Routine Activities Theory with Lifestyle Exposure Theory, often called Lifestyle-Routine Activities Theory, may provide a better framework to address how the opportunities for criminals to victimise individuals are produced by their everyday routines and lifestyle behaviours which expose them to risk (Reyns et al., 2011). Its central premise can be applied to cyberspace because the everyday routines and lifestyle behaviours that expose individuals to potentially being catfished by false identities or romanced by scammers using stolen selfies may simply include logging on to email, browsing the web or instant messaging over social media. Fortunately, technologies such as an antivirus or a Virtual Private Network can be considered capable guardian’s because they protect a user’s privacy, which along with restricting privacy settings on social media is essential to safeguarding online identities. “In online environments, the physical component of guardianship has been operationalized by measuring the presence of firewalls and security programs” (Reyns et al., 2011b). The same academic paper noted that restricting social media profiles is an effective preventative measure against cyber-stalking, “the odds of victimization are more than doubled for those who allow strangers to access their online profiles”

As criminological theories evolve to shape how we understand crime in modern society underpinned by cyberspace, plain old statistics can help illuminate the landscape to reveal more about the demographics of motivated offenders. The academic paper Identity Fraud Trends and Patterns showed a diversity of age, race, gender, and criminal backgrounds with almost half of the offenders (42.5%) being aged between 25 to 34 years of age at the time they were captured. This was followed by the 35 – 49 age group which makes up almost one third (33%) of offenders while the remaining 6% were aged 50 years or older. Of gender, one third of the offenders were female with males making up the bulk of the perpetrators. Approximately half of the cases in the sample used the Internet and/or other technological devices were in the commission of the crime (Gordon et al., 2007).

Financial institutions may be considered capable guardians to protect individuals against identity fraud because they not only monitor security threats and suspicious transactions but also reimburse victims in cases of small scale credit card fraud. Nevertheless, capable guardians have also fallen victim to the crime with the dataset from Identity Fraud Trends and Patterns revealing that while individuals accounted for 34.3% of the victims of identity fraud, the financial industry organisations such as banks and credit unions account for 37.1% of victims (Gordon et al., 2007). Even though social media is a favorite stalking ground for catfish and identity fraudsters, Facebook has shown a complete disregard for the welfare of their users whenever profits are concerned. To further protect potential targets from being victimised by identity related crimes, legislative bodies must regulate these social media monopolies until they provide capable guardianship to protect their users from motivated offenders. Finally, capable guardians that belong to the field of information technology, cybersecurity and law enforcement must engage in cyber awareness training to empower the wider community to give them the agency to protect themselves and provide guardianship to others.

References

Bertram, T., Bursztein, E., Caro, S., Chao, H., Feman, R. C., Fleischer, P., Gustafsson, A., Hemerly, J., Hibbert, C., Invernizzi, L., Donnelly, L. K., Ketover, J., Laefer, J., Nicholas, P., Niu, Y., Obhi, H., Price, D., Strait, A., Thomas, K., & Verney, A. (2019). Five Years of the Right to be Forgotten. Google Research. https://research.google/pubs/pub48483/

Clough, J. (2015a). Principles of Cyber Crime (Second Edition, pp. 219, 227). Cambridge University Press.

Clough, J. (2015b). Principles of Cyber Crime (Second Edition, pp. 230–232). Cambridge University Press.

Clough, J. (2015c). Principles of Cyber Crime (Second Edition, p. 211). Cambridge University Press.

Clough, J. (2015d). Principles of Cyber Crime (Second Edition, pp. 218, 229). Cambridge University Press.

Drew, J. M., & Farrell, L. (2018). Online victimization risk and self-protective strategies: developing police-led cyber fraud prevention programs. Police Practice and Research, 19(6), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2018.1507890

Finch, E. (2007). Problem of Stolen Identity and the Internet (From Crime Online, P 29-43, 2007, Yvonne Jewkes, ed. — See NCJ-218881). United States.

Franks, C., & Smith, R. (2020). Statistical Report Identity crime and misuse in Australia 2019. https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-08/sr29_identity_crime_and_misuse_in_australia_2019.pdf

Gordon, G., Donald, E., Rebovich, J., Choo, K.-S., Judith, B., & Gordon. (2007). Identity Fraud Trends and Patterns: Building a Data-Based Foundation for Proactive Enforcement (p. 2). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/21748215.pdf

Lynch, J. (2005). IDENTITY THEFT IN CYBERSPACE: CRIME CONTROL METHODS AND THEIR EFFECTIVENESS IN COMBATING PHISHING ATTACKS (pp. 259, 294.). https://btlj.org/data/articles2015/vol20/20_1_AR/20-berkeley-tech-l-j-0259-0300.pdf

Peretti, K. K. (2008). Data Breaches: What the Underground World of Carding Reveals. Santa Clara Computer & High Technology Law Journal, 25, 375. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/sccj25&div=16&id=&page=

Reyns, B. W., Henson, B., & Fisher, B. S. (2011a). Being Pursued Online. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(11), 1149–1169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811421448

Reyns, B. W., Henson, B., & Fisher, B. S. (2011b). Being Pursued Online. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(11), 1158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811421448Yar, M. (2005). The Novelty of “Cybercrime.” European Journal of Criminology, 2(4), 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/147737080556056