After two years of extensive consultations of the Privacy Act (1988)(Cth)(‘Privacy Act’)1, the Attorney-General’s Department mentioned the word consent 518 times in its Privacy Act Review (‘Report 2022’).2 The nuances and complexities surrounding this issue has led to calls for a consistent delineation of consent for data collection across all sectors of the Australian economy to reduce complexity for consumers and data holders. In practice, however, the novel and emergent ways in which individuals and society as a whole interact with the kaleidoscopic landscape of competing technologies makes a one-size-fits-all consent form exceptionally difficult to implement. This article therefore looks at high-level concepts such as notice and choice and default-off while also investigating the difficulties of implementing consent at a technical level across sectors and technologies.3 It also examines how the Consumer Data Right (‘CDR’) Scheme compares with the Privacy Act in creating certainty for industry while simultaneously increasing control of data for the individual.4

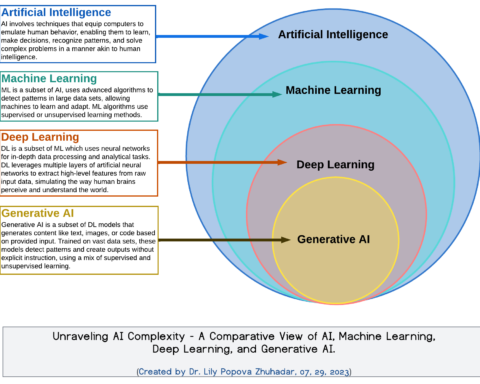

First and foremost, the article acknowledges the foresight of policymakers when legislating the Principles-based law of the Australian Privacy Principles (‘APPs’). The APP’s were created to be technology-neutral by design and introduced at a time when the modern Internet as we know it was in a much more rudimentary form.5 Policymakers may have been able to imagine the futuristic technology on the horizon with broad brushstrokes but could not have predicted specifics such as the way commonday domestic appliances connected to the Internet-of-Things (‘IoT’) transmit metadata over transnational Cloud instances which are then analysed by machine learning algorithms and Artificial Intelligence (‘AI’). Indeed, the increased penetration of IoT devices into every corner of the family home has led to the datafaction of Australian children, whereby digital data about minors is collected, analysed, profiled, tracked and commodified, often without consent.6

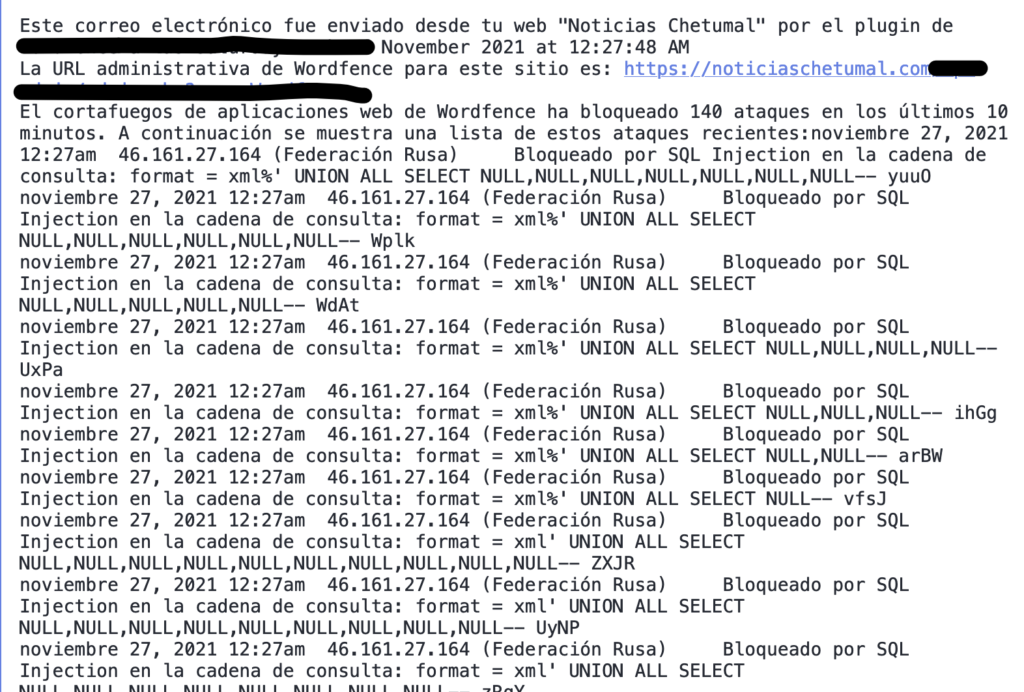

Another emerging technology challenging the limits of the Privacy Act is the rollout of facial recognition technology used to prevent theft in major Australian retailers. The technology matches an individual’s unique identifying information to a stored digital image.7 This biometric identifying information is considered “sensitive information” under the Privacy Act and is offered greater protections under APP 3, 6 and 11.8 Once collected, facial recognition can track customer visits, time of visits for pattern or behavioural analysis, and association with other shoppers.9 This data can then be merged with financial data or social media accounts and then sold to third parties on the massive data aggregation market.10 An investigation by CHOICE advocacy group into these practices found major Australian retailers use this technology, spurring an investigation of the privacy regulator OAIC.11

The Good Guys and Kmart stated customers must agree to the collection of their images as conditions of entry, as customers were notified through signage, but in reality ‘the collection, retention, and use of their images are not usually disclosed in any explicit way.’12 These retailer’s privacy policies revealed facial recognition technology was in use but these policies were online, difficult to find, and unlikely to be read by the vast majority of shoppers that enter the stores.13 Furthermore, CHOICE noted Kmart and Bunnings had physical signs alerting consumers to facial recognition technology, ‘but the signs were small, inconspicuous and would have been missed by most shoppers.’14

Notice and choice, often called notice and consent, is the current methodology for obtaining consent online.15 The notice presents a Privacy Policy or Terms of Use agreement to which the individual chooses whether to consent to or not.16 Informational privacy is the capability of determining for ourselves when others may collect and how they may use our information.17 This determination can be made when we give or withhold free and informed consent to a proposed collection of our data; otherwise, ‘you cannot determine for yourself what others do with your information’.18 Free and informed are keywords to consent because as the technological landscape becomes increasingly complex the ability of the layperson to fully comprehend how our data is collected is greatly diminished. Do adults understand the extent of datafication of their children when they consent to the terms and conditions to use Amazon’s Alexa in the family home? Does an individual know their biometric facial patterns are collected when they walk into a 7-Eleven and stored on the company’s private cloud?

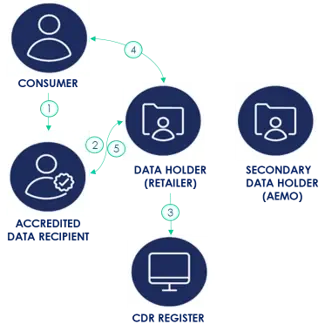

The CDR Scheme ensures that an accredited person ‘may only collect, use and disclose CDR data with the consent of the consumer’ but allows ‘specific categories of consents’.19 A look at Microsoft’s Azure documentation, however, reveals the complexities for industry when implementing consent for CDR on the cloud at a technical level.20 The CDR Scheme has rolled-out in the banking and energy sectors but has not been road tested in industries where transnational companies such as Amazon and Facebook wield overwhelming market power. There is a lack of scholarly information on whether consumers would be able to gain access to security information, such as biometric data from facial recognition, once the CDR Scheme is rolled out in more designated industries. However, if the CDR allows parents the means to access the personal data of IoT devices such as Amazon’s Alexa to curtail the datafaction of their children it will be a major win for consumers and address shortfalls in the Privacy Act.

The shortfalls of the Privacy Act were addressed in the Digital platform services inquiry (‘Platform Report’)21 which recommends replacing “reasonable steps” with more detailed rules about notification requirements, strengthening user consent by mandating platform default settings to be preselected to “off”, which then requires a positive act of consent to collect user data.22 The Platform Report was also concerned that the principles-based regulation of the APP’s, ‘under which obligations are formulated as high-level principles rather than detailed rules’, confers too much discretion on major companies governed under the act.23

The APP’s have served Australia well during a period of great technological change but it’s time to strengthen them. As society grapples with a new Orwellian era of invasive facial recognition while the rise of AI threatens to upend entire industries, the government needs to get consent right. It is too early to tell whether the CDR Scheme will address the shortfalls in the Privacy Act as more designated industries are regulated under its legislation. This means fine tuning the principles-based law of the APP’s is necessary as the next waves of technological innovation may prove to be even more disruptive.

- Privacy Act (1988)(Cth)(‘Privacy Act’). ↩︎

- Attorney-General’s Department, Privacy Act Review (2022)(‘Report 2022’). ↩︎

- (emphasis added). ↩︎

- Competition and Consumer (Consumer Data Right) Rules 2020 (Cth)(‘CCR 2020’). ↩︎

- Privacy Act n1. ↩︎

- Pangrazio, L., & Mavoa, J. ‘Studying the datafication of Australian childhoods: learning from a survey of digital technologies in homes with young children’ (2023) 0(0) Media International Australia. ↩︎

- Desmond, D. (2022). Bunnings, Kmart and The Good Guys say they use facial recognition for “loss prevention”. An expert explains what it might mean for you. The Conversation, 15 June 2022. ↩︎

- Privacy Act, s APP 3. ↩︎

- Idib. ↩︎

- Idib. ↩︎

- OAIC, ‘OAIC Opens Investigations into Bunnings and Kmart’, OAIC (10 March 2023). ↩︎

- Desmond, D. (2022). Bunnings, Kmart and The Good Guys say they use facial recognition for “loss prevention”. An expert explains what it might mean for you. The Conversation, 15 June 2022. ↩︎

- Blakkarly, Jarni, ‘Kmart, Bunnings and the Good Guys Using Facial Recognition Technology in Stores’, CHOICE (14 June 2022). ↩︎

- Idib. ↩︎

- Robert H. Sloan and Richard Warner, ‘Beyond Notice and Choice: Privacy, Norms, and Consent’ (2014) 14(2) Journal of High Technology Law 370. ↩︎

- Idib. ↩︎

- Idib. ↩︎

- Idib. ↩︎

- OAIC, ‘Chapter C: Consent – the Basis for Collecting and Using CDR Data’, OAIC (10 March 2023) <https://www.oaic.gov.au/consumer-data-right/consumer-data-right-guidance-for-business/consumer-data-right- privacy-safeguard-guidelines/chapter-c-consent-the-basis-for-collecting-and-using-cdr-data >. ↩︎

- 20 Rolf Tesmer, ‘Implementing Consumer Data Right (CDR) Solutions on Azure’, Microsoft (28 July 2022) <https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/azure-architecture-blog/implementing-consumer-data-right-cdr-solutio ns-on-azure/ba-p/3096375>. ↩︎

- The Digital platform services inquiry (‘Platform Report’) ↩︎

- Platforms Report, n 21, 437–439. ↩︎

- Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC), For Your Information: Australian Privacy Law and Practice, Report 108 (May 2008) 233–254. ↩︎